AMAZING SPECIES

Grand Cayman Blue Iguana:

The stunning azure shades of the Grand Cayman Blue Iguana (Cyclura lewisi) are at their brightest during the breeding season. They remain dark grey when cold, camouflaging among their rocky habitat. This species is endemic to Grand Cayman, where it is the largest native land animal, at 1.5 metres long. This also makes it amongst the largest lizards of the Western Hemisphere, and with a life span of over 50 years it is amongst the longest-living. Since European colonisation, this iguana has faced intense threats including habitat destruction and predation by feral and free-roaming dogs and cats. By 2002, there were fewer than 25 adults surviving in the wild. A captive breeding programme brought the species back from the brink of extinction, with iguanas released into protected areas. However, threats outside of these areas have intensified over the past decade, and the fragmented network of small protected areas is not sufficient to provide long term security for the species: for this, habitat will need to be restored and feral mammal populations controlled island-wide. Community involvement is also important – for example, local residents have assisted the conservation programme by harvesting wild plants to feed the iguanas in the conservation breeding facility.

Fan Mussel

The Fan Mussel (Pinna nobilis), also known as the Noble Pen Shell, is one of the world’s largest living bivalves, with its two-part hinged shell reaching up to 1.2 metres in length. Endemic to the Mediterranean Sea, this mollusc inhabits sea grass meadows and sandy or rocky bottom habitats at depths of up to 60 metres. It attaches itself to the seabed using extremely fine and tough silk-like byssus threads, with the inside of its shell lined with mother of pearl. The byssus threads have been used and traded for millennia to produce textiles of the highest value. The species has long faced many threats, including overexploitation, habitat loss, pollution, and invasive species. Since 2016, the parasite Haplosporidium pinnae and associated infectious diseases have spread eastward from the Spanish Mediterranean Sea, causing mass mortality of up to 100% of affected populations. It is now present throughout the mollusc’s range, though deeper populations below 50 metres may be impacted less. To mitigate the effects of Haplosporidium pinnae and limit its spread, there urgently needs to be more research into this parasite, as well as the Fan Mussel populations that appear to have better resistance to it. Population recovery is expected to be slow even in the absence of disease, and habitat protection and conservation breeding may be vital to boost this.

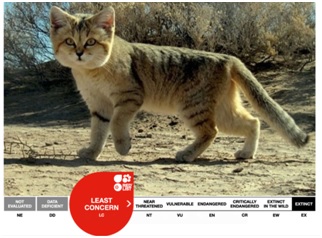

Sand Cat

The Sand Cat (Felis margarita) is the only cat species found primarily in true desert, withstanding extreme temperatures between -25°C to 50°C across northern Africa and southwest and central Asia. Its thickly furred feet enable it to cope with sand surface temperatures up to 80°C. The Sand Cat does not need drinking water, as it can satisfy its water requirements through its diet of mainly small rodents. It is difficult to estimate the number of Sand Cats, as they live at low population densities in inhospitable conditions that are often difficult to census. However, there are reports of local declines, and there are no recent records from several countries within the species’ range. Major threats include habitat loss and degradation due to human settlement and disturbance activity, for example through fencing and livestock grazing. Declines in prey species, as livestock grazing reduces the natural vegetation small mammals live on, combined with competition for prey and disease transmission from feral and domestic cats and dogs, further threaten the Sand Cat. Accurate surveys are urgently required to monitor this cat’s population, and studies on its habitat and ecology are needed to promote effective conservation actions. Protection from hunting and trade, plus captive breeding, are important measures supporting this species.

Sunflower Sea Star

.jpg)

The Sunflower Sea Star (Pycnopodia helianthoides) is among the largest and fastest sea stars in the world, with its 16 to 24 limbs reaching a diameter of up to one metre. It lives along the vast majority of the Pacific coast of North America. Sunflower Sea Stars are opportunistic hunters of a wide range of marine invertebrates, and in some areas are important predators that regulate surrounding ecosystems. As a predator of sea urchins, which graze kelp, the species helps keep kelp forests healthy. Over five billion Sunflower Sea Stars have died since the outbreak of sea star wasting syndrome in 2013. The population declined over 90% and disappeared from the southern half of its range. The cause of this disease is unknown, but there is evidence that warmer temperatures played a role. A lack of natural recovery means conservation measures are likely necessary to recover this species. Captive rearing has proven successful, and reintroduction is being explored. Further, it is critical to discover the cause of sea star wasting syndrome to ensure conservation actions go unthwarted. Long-term research, international collaborations, and stopping climate change are critical for maintaining biodiversity and healthy ocean ecosystems into the future.

Kraaifontein Spiderhead

Just a single Kraaifontein Spiderhead (Serruria furcellata) plant is known to remain in the wild, following habitat loss to urban and industrial development of Cape Town, South Africa. This shrubby plant grows in fynbos, the native vegetation of the Western Cape region renowned for its exceptionally high plant diversity and endemism. As with many other longlived fynbos species, this plant is adapted to survive fires by resprouting from underground, and seeds also germinate from underground. However, no seedlings of this species have ever been observed: it is common for long-lived fynbos species that are adapted to survive f ire through resprouting to also naturally show poor recruitment from seed. Nearly all of this species’ habitat has been irreversibly modified by urban and industrial development over the past century, with 38% of the habitat lost since 1990. The one remaining site is smaller than one hectare, and even this is severely degraded. Work to reintroduce the species to the wild is underway but faces significant challenges, with numerous plants not surviving the reintroduction. None of the reintroduced subpopulations have yet burnt so it remains to be seen whether they will successfully resprout after a fire. For long-term survival, seeds will also need to germinate successfully.

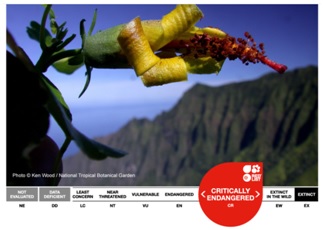

Hau Kuahiwi

Hau Kuahiwi (Hibiscadelphus woodii) is perched on the edge in more ways than one, following its rediscovery in 2019 using drone technology. This small Hawaiian tree occurs only on the island of Kauai, where it lives on cliffs. Hibiscadelphus species are closely related to Hibiscus, but their distinctive curved flowers have an abundance of nectar and do not fully open, which is thought to be an adaptation to pollination by honeycreepers. Predation and competition by non-native animals and plants drove the population to perilously low levels, and after three of the last four known individuals perished in a rockslide in the 1990s and the final plant died in 2011, the species was thought extinct. However, intensive drone surveys by National Tropical Botanical Garden in 2019 revealed a previously unknown population of another four individuals. Significant challenges remain – the plants are completely unreachable by humans, and although this may afford them some protection from invasive species, rockslides remain a threat. It is possible that future technology could enable drones to collect plant material in the hope of establishing an ex situ population of this Hibiscadelphus and other similarly imperilled species for their long term protection.

Mysterious Lantern Firefly

The Mysterious Lantern Firefly (Photuris mysticalampas) is one of two threatened species found only in the small, densely populated eastern state of Delaware, USA. This species’ name comes from the Latin “mystica”, meaning mystical or mysterious, and “lampas”, meaning flame or lantern. This is inspired by the males’ surreal courtship display, their prolonged greenish flashes appearing like distant torches, signalling slowly on and off through the dense forest understory. Adults emerge well after sunset from thick mossy hummocks. This species is restricted to tidal freshwater floodplains on the Delmarva Peninsula, where it is threatened primarily by sea level rise. The rate of sea level rise here is three or four times higher than the global average, with a rise of between 0.5 and 1.5 m expected by the year 2100. This would inundate most Mysterious Lantern Firefly habitats, which are less than 1 metre above the current sea level. Although several sites where it has been found are on protected public land, there are no specific conservation measures in place to protect the Mysterious Lantern Firefly. Ensuring forests remain alongside the floodplains where the fireflies live would be beneficial, to help mitigate the impact of rising water.

Brown Bear

Brown Bears (Ursus arctos) are by far the world’s most widely distributed species of bear, occurring in Asia, Europe, and North America in a diversity of habitats from sea level to 5000 metres. Their diet varies by region and season, and may be dominated by fish, ungulates, rodents, ants, roots, shoots, or fruits. They may hibernate for up to 7 months, but in some areas some individuals remain active all winter. Litters of 1-3 cubs are born during hibernation. Most brown bears inhabit large, stable northern populations in Canada, Alaska, or Russia. However, many of the world’s 44 separate populations are small, isolated, and at high risk of extinction, especially along the southern fringe of the range. Brown Bears reproduce slowly, with females having first litters at 4-12 years old and litters every 2-3 years thereafter, but in some populations this interval stretches to 4-6 years. Threats vary, but human-wildlife conflict is a recurring theme. In Europe, 4 of the 10 populations are assessed as Critically Endangered; however there is currently considerable effort in promoting human tolerance and financial investments aimed at improving prospects for their survival.

Tucuxi

The Tucuxi (Sotalia fluviatilis) is a freshwater dolphin species that lives in the Amazon River system in Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru. These small grey dolphins are usually found in small groups of up to around 6 individuals. They live in the main channels of large and medium sized rivers, but tend to avoid areas of fast-moving water, as well as flooded forests. Tucuxis prey on a variety of fish species. The number of Tucuxis is declining, with threats including death caused by fishing gear and habitat degradation due to dams and pollution. Eliminating the use of gillnets – curtains of fishing net that hang in the water – and reducing the number of dams in Tucuxi habitat are priorities to enable the population to recover. This species is included in international legislation such as the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS). There are also conservation action plans underway for the species at both national and continent-wide levels.

Moose

The Moose (Alces alces) is the largest living deer species in the world. It stands at over two metres tall and weighs up to 600 kilogrammes. The antlers, which are grown only by males over a few months and are shed every year, can weigh an average of 20-23 kilogrammes in prime-aged bulls. Moose are abundant across the Northern Hemisphere, in North America, Europe and Asia. These woodland herbivores are usually solitary, gathering only for mating. They also love wetlands and in some areas hold seasonal migrations, which can reach hundreds of kilometres, between habitats. Their hooves and long legs allow them to walk equally well in deep snow, marshes and ponds, and they also swim well. Unlike other deer species, Moose often give birth to twins and even, although rarely, to triplets. The main threat to the Moose is destruction and fragmentation of its habitat. In particular, forestry and agricultural practices have reduced the areas that these animals rely on. This species is protected internationally by the Bern Convention. It is also protected by national legislation in some areas and the population is actively managed in certain countries. Moose occur in a large number of protected areas across their range.

Platypus

Endemic to Australia, from eastern Queensland to King Island and Tasmania, the Platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) is one of the few egg-laying mammals, known as monotremes. Platypus numbers are decreasing. The Platypus is recognisable for its duckbill, webbed feet, paddle-shaped tail and thick waterproof fur. Its bill allows the animal to sense electric currents in water, which aids in catching prey. Male Platypuses have venomous stingers on their rear feet, which are used to compete against other males during the mating season. As it depends on freshwater habitats, the predominant threat to this species is the reduction in stream and river flows caused by droughts and water extraction. At the opposite extreme, it is also at risk from flooding, associated with climate change. Bank erosion and stream sedimentation caused by poor land management practices are another serious concern. Further threats include pollution in urban areas, accidental drowning in nets and traps, and predation by dogs, foxes and cats. The Platypus is legally protected across Australia and occurs in many national parks and reserves.

Titan Arum

Titan Arum (Amorphophallus titanum) has the largest flowering structure of any plant in the world, rising up to 3 metres from the ground. It is known as the ‘corpse flower’, from the infamous rotting smell when the plant is in bloom. This smell helps to attract pollinators during its short-lived flowering events. Although Titan Arum has a long life span of over 30-40 years, it flowers only occasionally and these events are often difficult to predict. Its native range in Sumatra, Indonesia is threatened by timber harvesting and creation of oil palm plantations. In addition, the myth about Titan Arum being a predator to people (due to the markings on the leaves’ stems which resemble a snake) leads to the destruction of the species when people find it growing in their farmlands. As the wild population declines, over 90 botanic gardens across 18 countries grow Titan Arum to support its conservation; it has flowered successfully around 100 times in captivity. It is also legally protected within Indonesia.

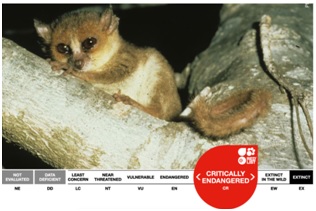

Madame Berthe’s Mouse Lemur

Madame Berthe’s Mouse Lemur (Microcebus berthae), named after the Malagasy primatologist Berthe Rakotosamimanana, is the smallest primate species in the world. Native to Madagascar like all lemurs, the species is restricted to the dry forest of Kirindy and Ambadira in west Madagascar. The major threats to this species are habitat loss and degradation due to slash and burn agriculture for maize and peanuts, the felling of trees for charcoal production and illegal logging. Despite the establishment of the Menabe-Antimena Protected Area over the range of Madame Berthe’s Mouse Lemur, as of 2020, the threats to this species are not under control. If deforestation continues at the same rate as during recent years, the remaining habitat and Madame Berthe’s Mouse Lemur might be lost before 2030. Several NGOs and institutions are active with development and conservation projects in the area. For example, Madame Berthe’s Mouse Lemur has been a flagship species in an education and awareness programme conducted with local youth. In recent years, there have been more intensive forest patrols across remaining forest fragments.

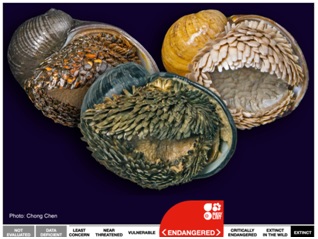

Scaly-foot Snail

The Scaly-foot Snail (Chrysomallon squamiferum) is the first species endemic to deep-sea hydrothermal vents to have entered the IUCN Red List of Threatened SpeciesTM. It is the first animal to be listed as Endangered due to deep-sea mining. Some of the remarkable features allowing it to thrive in its extreme environment include the largest heart relative to its size in the animal kingdom, and an iron-infused armour. This species is only known from three locations on deep-ocean ridges in the Indian Ocean, between 2,400 to 2,800 metres below sea level. Living in exceptionally hot active black smokers and diffuse flow sites, the Scaly-foot Snail has been found to occupy an area of less than 0.02 km2. Due to its highly specific habitat, the maximum area it is estimated to potentially inhabit does not exceed 300 km2. There is ongoing investigation into the development of deep-sea mining in two of the three locations the Scaly-foot Snail has been found. There are rising concerns that if mining is permitted, the habitat could be severely reduced or destroyed. While the conservation significance of this addition to the Red List has been widely reported in the media, there are no conservation actions currently in place at any of the vent fields in the Indian Ocean. Further research into the Scaly-foot Snail would be beneficial to improve understanding of the species, its threats and conservation.

(Source: https://www.iucnredlist.org/resources/grid/amazing-species)